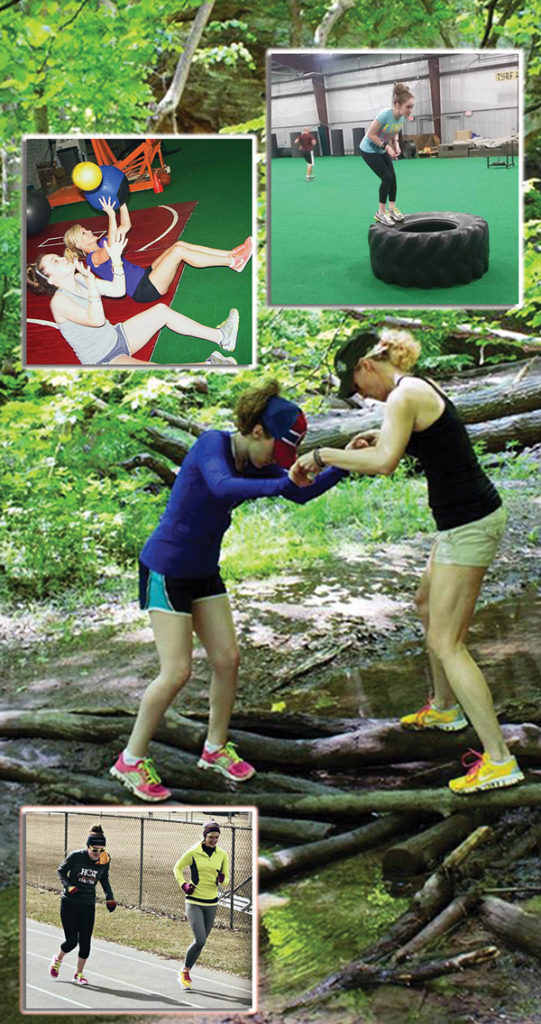

When Kiley Lyall was growing up, her mother, Kathleen Lyall, joined her in therapy and other activities. She continues to run alongside Kiley in road races. (Photos courtesy of Kathleen Lyall.)

A normal gait is often the goal for children with neuromuscular disorders and mobility impairments, but research suggests this may come at the price of children’s positive self-identity. These issues are leading some practitioners toward more holistic, family-centered approaches to walking.

By Brigid Galloway

As an occupational therapist in children’s rehabilitation for more than 20 years, Gail Teachman, PhD, observed a troubling phenomenon: Parents of children with mobility issues, including those caused by cerebral palsy (CP) and degenerative neuromuscular disorders, often passed along the messages embedded in children’s rehabilitation that suggest their kids were somehow defective and in need of “fixing.” It wasn’t intentional. The parents were worried about their children’s long-term happiness. Yet, the desire for their child to meet age-appropriate mobility milestones, or to walk with a “normal” gait, created mixed effects—some harmful.

“That’s the heartbreaking part for these families. Social expectations reinforce the message that something is wrong with their child, and that as a ‘good’ parent they should try everything possible to fix their child,” said Teachman, a Canadian Institute of Health Research postdoctoral fellow for Views on Interdisciplinary Childhood Ethics at McGill University in Montréal.

“A top goal is for their child to walk, regardless of the cost, or the burden that places on their family or on the child. After all, the notion of ‘overcoming’ disability is reinforced over and over in popular culture,” she said.

That burden can have lasting effects on the child. As Teachman followed up with the children she worked with at Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital in Toronto, Canada, she saw their attitudes develop in the context of the reality of their everyday lives.

Clinicians need to collaborate with parents intensively and use their expert knowledge to understand the child’s real-world partici-pationproblems.

–BarbaraPisǩ ur,PhD

In a 2012 study published in Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, Teachman and lead researcher, Barbara E. Gibson, PhD, examined the symbolic value of walking.1 (Gibson has also written about this topic for LER. See “The value of walking in children with CP: A matter of perception,” January 2013, page 14.)

Participants included six Canadian children with CP, aged 9 to 18 years, with gross a motor functional classification system (GMFCS) level of III or IV. They interviewed the children and one of each child’s parents (five mothers, one father). The children’s accounts revealed how, over time, and with continued exposure to negative values, they came to look at themselves as a burden to society.

Teachman contends the high value placed on walking is related to expectations about what is considered normal childhood activity. Even when children with mobility issues are physically included in mainstream activities, they may still experience exclusionary and even hostile social interactions.

“Disability is almost universally assigned a negative value,” Teachman said. “These assumptions are deeply imbedded in all of us. When children are repeatedly exposed to the sense that being disabled is a negative thing, they internalize the sense of ‘I’m lesser, broken, or there’s something wrong with me,’ because they are not able to do things in the same way that so-called typically developing children do.”

“Disability is almost universally assigned a negative value,” Teachman said. “These assumptions are deeply imbedded in all of us. When children are repeatedly exposed to the sense that being disabled is a negative thing, they internalize the sense of ‘I’m lesser, broken, or there’s something wrong with me,’ because they are not able to do things in the same way that so-called typically developing children do.”

According to the study, the children were more likely to be accepting or even excited about the alternate modes of mobility that marked them as “disabled” than their parents. Likewise, children “conveyed much more ambivalent beliefs about the value of walking than their parents.” Some parents were able to counter society’s idealization of normal by shifting their own perspectives; for example, coming to perceive their child’s mobility challenges as normal for that child, and then passing this attitude along to their child and others who interacted with their child.

Teachman said healthcare providers can play a role in relieving the stigma attached to a child’s disability by encouraging children and parents to talk about difficult subjects, such as how the family feels about the child using a wheelchair or alternative ways of being mobile, such as crawling.

“Clinicians can discuss these kinds of values and point out how they can shift,” Teachman said. “You can support young people and their families to develop more positive disability identities.”

Communication gap

Collaboration between clinicians and parents, who have knowledge and understanding of their child, may be key to changing the value system around the goal of attaining normal gait and helping kids with mobility challenges achieve as much function as possible.

A 2012 scoping review in BMC Pediatrics2 explored parents’ actions, challenges, and needs as they related to enabling their children’s participation in daily life.

The authors identified 14 studies of 146 Dutch parents of a child aged 4 to 12 years with a neurological nonprogressive physical disability that focused on the actions, challenges, and needs of the parents. “We discovered a distinction between parental priorities and those of therapists treating the children,” said first author Barbara Piškur, PhD, senior researcher at the Centre of Research Autonomy and Participation for Persons with a Chronic Illness & Department of Occupational Therapy at Zuyd University, Heerlen, the Netherlands.

“We saw a pattern that the parents are alert and occupied with their [child’s] environments [social, home, school, rehabilitation, etc],” Piškur said. “They described that [healthcare] professionals lacked knowledge or understanding about what their children need to participate.”

Parents perceived a gap in understanding between the environments where their children lived and the environments in which practitioners examined or worked with their children. “I strongly believe [practitioners] working with children with mobility disorders need to collaborate with parents intensively to understand the real participation problems of the child, to set up goals together with the child, and to use the expert knowledge of parents,” said Piškur.

Piskur and colleagues found healthcare professionals rarely provided information about suitable leisure activities. Moreover, parents stressed that, often, clinicians regarded leisure activities as additional therapy rather than something children do with other children for fun.3

Piskur and colleagues found healthcare professionals rarely provided information about suitable leisure activities. Moreover, parents stressed that, often, clinicians regarded leisure activities as additional therapy rather than something children do with other children for fun.3

“The therapists were focused on the functioning of a child as a person, but the parents were far more focused on how the child participates in different activities in different contexts,” Piškur said. “The parents were keenly aware that, even if he may walk well, if he’s isolated and lonely and doesn’t have friends, that will have a big impact on the child and his future.”

Piškur believes more collaboration between practitioners and parents is required, as is more focus on the demands of specific environmental settings. She recommends therapists seek more exposure to the child’s home and school environments so they can match techniques and advice with those contexts. By experiencing the challenges the child faces, practitioners could tailor therapy to his or her actual needs.

Teachman agreed clinicians often have a different idea of “success” than parents. According to a 2014 article published in Physical & Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics,3 parents of children with CP were often more concerned with the goal of independent walking than other goals, while therapists “believed walking was important, regardless of its appearance or what gait aids were used because it increased accessibility.”

Creating positive disability identities is a key goal—for parents, clinicians, and their young patients. It’s an especially delicate balance for clinicians to manage realistic expectations alongside parents’ hopes.

One method Teachman has found effective is to facilitate children’s relationships with other children who have similar mobility or functional issues.

“I’ve worked with young people who have never met anyone else who was encountering some of the same physical challenges they experience,” Teachman said. “Meeting other people who use the same mobility or assistive devices can be quite powerful; older youths can mentor younger kids, and this can contribute to a positive sense of their own worth.”

Follow the leader

Paul Jordan, DPM, has a handle on both optimism and expectations. For the past 37-plus years in Long Island, NY, he’s specialized in pediatric biomechanics, orthoses, and surgery for children with neuromuscular and neuromotor disorders. He refuses to make predictions about mobility based on an infant’s magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) results or initial examination.

“An MRI says nothing about the child’s ability and will, and the parents and their approach,” he said. “The parents have so much to do with it. If the parents hear their child is never going to walk when it’s first born, where are they going to set their sights? I tell parents to set their goals high, and if we make it fifty percent of the way, wonderful. My guess is, we’ll make it further.”

Jordan’s goal is not whether a child will walk “normally,” but rather that he or she will be able to do the things they would like to do. He spends 90 minutes or more with every child, watching them play and observing their movement and interaction with the environment, and involving siblings when possible.

Jordan’s goal is not whether a child will walk “normally,” but rather that he or she will be able to do the things they would like to do. He spends 90 minutes or more with every child, watching them play and observing their movement and interaction with the environment, and involving siblings when possible.

He advocates listening to children to find out what’s most important to them. “The kids teach me,” he said. “They don’t care if they do an activity differently, they just want to do it. As they get older, you empower the kids to make choices.”

Jordan builds custom orthoses to accommodate the comfort level and specific activities in which a child wants to participate. For example, after performing surgery on a young patient with spastic diplegia that enabled him to walk for the first time, Jordan removed his casts and fit him in ankle foot orthoses to help him ambulate.

“After a year, he came back for a new set of braces,” said Jordan. “I said, ‘I don’t want to put you in them. You’re eleven and half years old [and don’t need them now].’ He said, ‘I can walk farther distances and they help me play baseball.’ So I let him choose. We keep changing the design and shape of them to suit his function and needs.”

Jordan frequently consults with neurosurgeons, pediatric orthopedists, and therapists, sharing his understanding of each child’s needs. “Together, by being more creative and open-minded, we can see the child from a different perspective,” he said. “All kids dream, and my goal is to see how I can help them make some of those dreams come true.”

Jordan tries to dispel the naysayers—including other healthcare professionals and parents—who may have told the child they can’t do the activities they long to perform. “I say, why not? I introduce them to ways they can learn to surf, sail, or skateboard—and they do can it—but they do it differently,” he said. “They don’t care if they do it differently, they just want to do participate.”

Sometimes adaptive equipment is required, but Jordan encourages children to participate by exploiting their abilities rather than focusing on their perceived disabilities. Either way, his goal is for them to participate with kids of the same age who don’t have mobility impairments.

No expectations

For some, allowing a young patient to lead the approach to treatment based on their real-world needs and environment can produce impressive results. Krishna Kalmese, BS, kinesiologist and owner of Kalmese Wellness Studio in Bourbonnais, IL, uses this technique as he works with children with disabilities, including those who have mobility issues caused by CP, multiple sclerosis, and other neuromuscular conditions. His approach is one of patience and gradual progress based on the individual, rather than time-driven expectations.

He noted that, parents who set a specific time frame for therapeutic goals hinder their child’s progress. “Our society introduces speed into goals,” he said. “I’ve had young people who could have done great things quit therapy because their parents thought they should be progressing further, faster.”

He noted that, parents who set a specific time frame for therapeutic goals hinder their child’s progress. “Our society introduces speed into goals,” he said. “I’ve had young people who could have done great things quit therapy because their parents thought they should be progressing further, faster.”

Kalmese begins each session by checking in with his young clients to see how they’re doing physically and emotionally. Taking their lead, he selects exercises that best fit their ability at that time. “I encourage them frequently,” he said. “For example, floor exercises open their hips, and balance work helps build confidence. The approach is always to remain positive, and I try to avoid stress and discomfort so they want to keep coming back.”

One of Kalmese’s longtime clients, Kiley Lyall, was born with epilepsy and diagnosed with CP (GMFCS level II) and autism when she was aged 3 years, the same time she finally began to walk. Even then, she frequently lost her balance. Her mother, Kathleen Lyall, was told by clinicians that her daughter’s physical, emotional, and mental abilities would never advance beyond that of a typical 8-year-old. Today, Kiley, aged 24 years and living in a Chicago suburb, runs conventional marathons alongside normally abled athletes.

“No one told her ‘You’re going to love working out,’” Kalmese said. “It was an aha! moment. She developed it on her own. You could see how she started to open up and become herself.”

Kiley’s combination of conditions made balance, let along walking, difficult. But, after winning a Special Olympics relay when she was aged 8 years, she embraced distance running. In addition to Kalmese’s fitness and nutritional guidance, Kiley began ongoing physical therapy with a running coach. Her mother soon discovered that running helped improve her daughter’s balance and boosted her confidence. When Kiley ran, she no longer felt different or left out. She was just another runner in the pack.

“It was hard when she was little,” Kathleen Lyall said. “It’s not an easy road, but if you listen to your child—and that’s the key—they will lead you into the right direction.”

With Kalmese’s help, the Lyalls found ways to follow Kiley’s lead and encourage her activity. By listening to their daughter and helping her define her own goals, she exceeded all expectations. Kiley now works part time at a hair salon. When she showed talent in photography, Kathleen helped her launch a portrait business.

“Not in a million years did we think that Kiley would be doing the things she does today,” Lyall said. “When we have unrealistic expectations of our children and we push them, it’s not going to work. If they love to do it, they will succeed at it, whether they are specially challenged or not.”

Today, Kiley (who aspires to become a personal trainer) continues to push herself to do more in the gym, and encourages other people—with and without disabilities—to reach their goals. In January, she appeared on the cover of Women’s Running after being selected from more than 4000 entries in its annual Cover Runner contest. But, even when the attention is positive, Kiley sometimes struggles with being singled out.

“Kiley has a distinctive gait, so when she runs races sometimes people come up and encourage her,” said Lyall. “She just wants to be treated like everyone else and be accepted for what she can do because of who she is, not because she has a disability.”

Brigid Galloway is a freelance writer in Birmingham, AL.

1. Gibson BE, Teachman G. Critical approaches in physical therapy research: investigating the symbolic value of walking. Physiother Theory Pract 2012;28(6):474-484.

2. Piškur B, Beurskens AJHM, Jongmans MJ, et al. Parents’ actions, challenges, and needs while enabling participation of children with a physical disability: a scoping review. BMC Pediatrics 2012;12:177.

3. LeRoy K, Boyd K, De Asis K, et al. Balancing hope and realism in family-centered care: Physical therapists’ dilemmas in negotiating walking goals with parents of children with cerebral palsy. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr 2014 Jun 12. [Epub ahead of print]